Sometimes, only small changes are required for potentially huge downstream effects.

Most academics would agree that the way scholarship is done today, in the broadest, most general terms, is in dire need of modernization. Problems abound from counter-productive incentives, inefficiencies, lack of reproducibility, to an overemphasis on competition at the expense of cooperation, or a technically antiquated digital infrastructure that charges to much and provides only few useful functionalities.

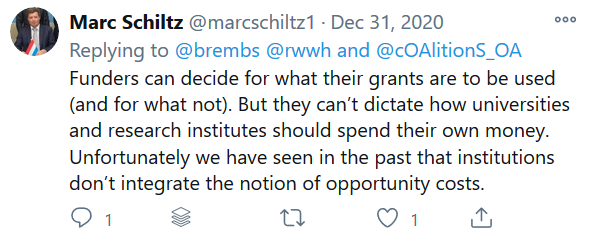

For a few years now I have been arguing that in order to accomplish change in scholarly infrastructure, it likely is an inefficient plan by funding agencies to mandate the least powerful players in the game, authors (i.e., their grant recipients). The legacy publishing system still exists because institutions pay for its components, publishers.

So this is essentially what happened instead of us sitting down and thinking how we could spend our money in the most technologically savvy way to the benefit of science, scholars and society. A generation later, roughly US$300 billion poorer and none the wiser, it seems.

Over the last ten years, scientific funding agencies across the globe have implemented policies which force their grant recipients to behave in a compliant way. For instance, the NIH OA policy mandates that research articles describing research they funded must be available via PubMedCentral within 12 months of publication. Other funders and also some institutions have implemented various policies with similar mandates.

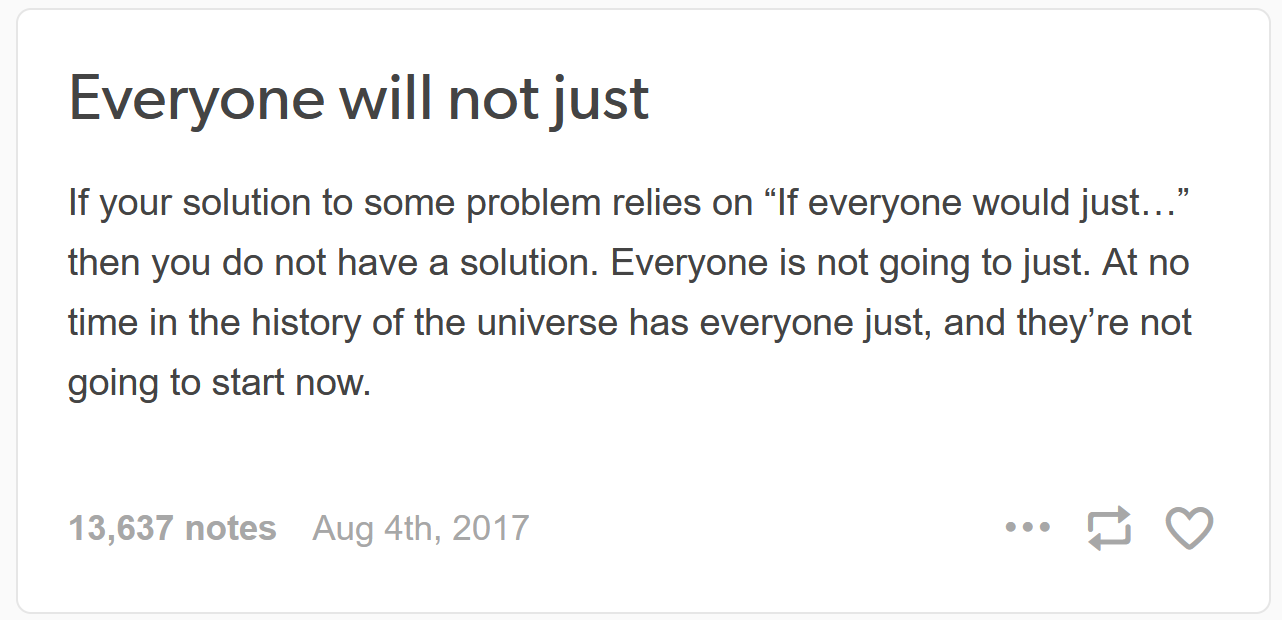

Mike Taylor wrote about how frustrated he is that funders don’t issue stronger open access mandates with sharper teeth. He acknowledges that essentially, the buck stops with us, the scientists, but mentions that pressures on scientists effectively prevent them from driving publishing reform.