Forgive me if I am wrong, but I had thought that Higher Education was for adults, albeit young ones. On the pages of CSTonline we have, from time to time, talked about the problem of teaching TV Studies at University.

Forgive me if I am wrong, but I had thought that Higher Education was for adults, albeit young ones. On the pages of CSTonline we have, from time to time, talked about the problem of teaching TV Studies at University.

I don’t have much time for WikiLeaks or its narcissist-in-chief. Anyone surprised by their revelations (consider, you know, the history of the US government domestically and internationally since, oh, 1776) or his conduct (q.v. Julian Assange v. Swedish Prosecution Authority) is naive in the extreme.

Previous blog posts by my Adapt colleague, Professor James Bennett, on our social media research project have focused on ‘Social Media in the Television Workplace’ and social media’s impact on the production of live TV. This post shifts our focus from The Voice, as a ‘shiny floor show’ with social production by a discrete digital unit, to draw on our subsequent ethnographic observations of Channel 4’s Sunday Brunch gallery

Here’s the pitch. Game of Thrones meets Mad Max in a post-apocalyptic wilderness somewhere North of Adelaide where a giant panda is on a lonely quest to atone for his wrongs to humanity.

Department of Communication and Media, March 16th 2017 Organisers: Annette Hill, Michael Rübsamen, Tina Askanius and Zaki Habibi Fear is a key factor in today’s media landscape. A dynamics of fear frequently frames the news about the environment or immigration, it dominates discourses of security and surveillance, and it permeates people’s lived experiences in precarious times.

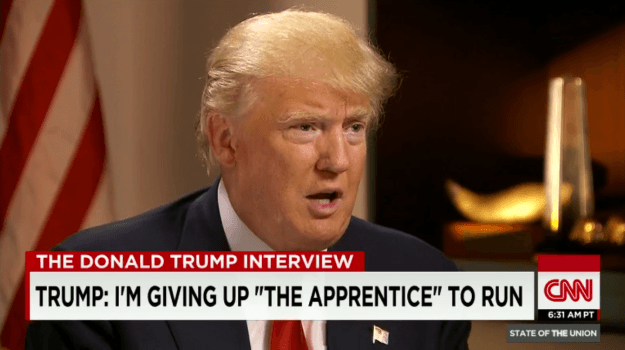

Media played an integral, deeply complicated role in the recent presidential campaign, with Donald Trump’s candidacy and win fundamentally transforming the relationship between the media, culture, and politics.

The recent General Election in the US shocked politicians, pollsters, political scientists, and progressives alike. How did two absurd people end up as the principal parties’ picks , and why will the most ridiculous coiffure since Jefferson’s enter the White House in January?

There’s been quite a bit of trending lately on Facebook about saving the BBC. I’ve done my fair bit of sharing a picture of the wonderful David Attenborough leaping to the broadcaster’s defence. Others have shared the BAFTA speeches which this year were full of praise for the corporation. This is perhaps no surprise since several programmes that won were made for or indeed by the BBC.

Much has been written about the way in which social media has reinvigorated live television, particularly from the perspective of the audience (for example, Liz Evans, Sheryl Wilson, or Inge Sø renson). But much less is known, or written, about how the liveness of social media has affected the production of a range of forms of live television that have made increasing use of platforms such as Twitter, Facebook, Periscope, Instagram and

British television fans need no convincing of James Corden’s smiley, shiny, naughty wonderful. From host to writer to actor to bloody nice singer and dancer, he’s annoying good at many showbizzy things (plus, he seems just annoyingly nice generally). Gavin and Stacey was when I really got to know him.