With the 2014 centenary of the First World War already being trailed, the BBC’s move to a steampunk view of history is fascinating.

With the 2014 centenary of the First World War already being trailed, the BBC’s move to a steampunk view of history is fascinating.

Last week (Friday 8 th November, to be exact) marked the 25 year anniversary of the UK broadcast of Scott and Charlene’s wedding in Australian soap opera, Neighbours , watched by almost 20 million viewers at the time.

The media’s power to imbue particular places with the authority to be sites of interesting and pertinent stories fascinates me. It also feels like it is a process in operation everywhere. This summer, an article in The Times caught my eye because it was titled, ‘Thank goodness Edinburgh hasn’t gone all Scottish’. It’s a classic bit of journalistic word-play, but for the life of me I couldn’t grasp why Edinburgh should disavow its Scottishness.

Starting work on the three year AHRC project ‘The History of Forgotten TV Drama in the UK’ at Royal Holloway has led me to think a lot about to what extent I remember television myself, and the reliability of my own memory. A widespread false memory syndrome can afflict even programmes that are ostensibly well remembered.

This blog is primarily inspired by Christine Geraghty’s recent CST post ‘Re-Appraising the Television Heroine’ and also what Douglas Howard refers to as the ‘crossroads’ that has been reached in US quality television.

Television. So often derided or adored for its alleged properties of distraction or pleasure. Blamed by pediatricians for making children weigh more than is fashionable in evidence-based public policy. Criticized by some cultural critics for diverting the young, the middle-aged, the firm, and the infirm from attending to real matters of state or heart. Valorized by corporations as a guaranteed source of revenue.

Horror is not a genre often traditionally associated with television, although as Helen Wheatley, Stacey Abbott and Lorna Jowett have pointed out television has a long history of telling horrific tales. It’s also not a genre with which I have much affinity or experience, being much too terrified to be able to watch most horror cinema.

Outside a cold wind is blowing; the rain batters my window pane, and the shades of night are falling fast. All of which can mean but one thing: autumn has arrived, and with it the Saturday tea-time schedule. Yes, I’m aware that weekend programming is not exactly suspended for the rest of the year, but I always feel there’s something rather special about the run-up to Christmas;

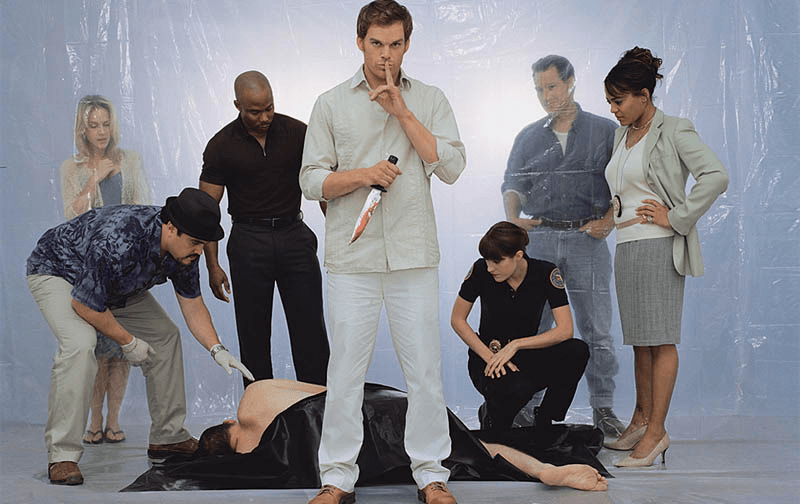

Internalising emotions, keeping secrets from friends and family, stalking men at night, and leading a double life. No, this is not Queer as Folk (2000-2005); this is Dexter (2006-2013) – a popular TV series that just reached its rather lackluster climax at its highly anticipated eighth season.

It was the recent conference at Hastings, ‘Raymond Williams and John Logie Baird – Television, Technology and Cultural Form’, organized by Professor Deborah Philips of the University of Brighton, which sent me back to Bill Brand (Jack Shepherd), hero of Trevor Griffiths’ 1976 series, who, as newly elected Member of Parliament for Leighley, wrestled with the question of whether the House of Commons was the best place to make a push for his brand

Jo Brand and Lee Mack were part of a panel discussing current issues in the profession at the launch of a new Centre for Comedy Studies Research. Dr John Roberts, chairing, posed the first question; what should a