My institute is going through various reviews of staff performance and, frankly, I'm feeling somewhat vulnerable given my somewhat unorthodox (at least amongst my colleagues) approach to doing science.

iPhylo

Interest in archiving data and data publication is growing, as evidenced by projects such as Dryad, and earlier tools such as TreeBASE. But I can't help wondering whether this is a little misguided. I think the issues are granularity and reuse. Taking the second issue first, how much re-use do data sets get? I suspect the answer is "not much". I think there are two clear use cases, repeatability of a study, and benchmarks.

Quick demo of the mockup I alluded to in the previous post. Here's a screen shot of the article "PhyloExplorer: a web server to validate, explore and query phylogenetic trees" (doi:10.1186/1471-2148-9-108) as displayed as a web-app on the iPad.

Apple's iBooks app is an ePub and PDF reader, and one could write a lengthy article about its interface. However, in the context of these posts on visualising the scientific article there's one feature that has particularly struck me. When reading a book that cited other literature the citations are hyper-links: click on one and iBooks forwards you (via the page turning effect) to the reference in the book's bibliography.

Thinking about next steps for my BioStor project, one thing I keep coming back to is the problem of how to dramatically scale up the task of finding taxonomic literature online. While I personal find it oddly therapeutic to spend a little time copying and pasting citations into BioStor's OpenURL resolver and trying to find these references in BHL, we need something a little more powerful.

Hot on the heels of Geoffrey Nunberg's essay about the train wreck that is Google books metadata (see my earlier post) comes Google Scholar’s Ghost Authors, Lost Authors, and Other Problems by Péter Jacsó. It's a fairly scathing look at some of the problems with the quality of Google Scholar's metadata. Now, Google Scholar isn't perfect, but it's come to play a key role in a variety of bibliographic tools, such as Mendeley, and Papers.

While thinking about measuring the quality of Wikipedia articles by counting the number of times they cite external literature, and conversely measuring the impact of papers by how many times they're cited in Wikipedia, I discovered, as usual, that somebody has already done it. I came across this nice paper by Finn Årup Nielsen (arXiv:0705.2106v1) (originally published in First Monday as a HTML document, I've embedded the PDF from arXiv

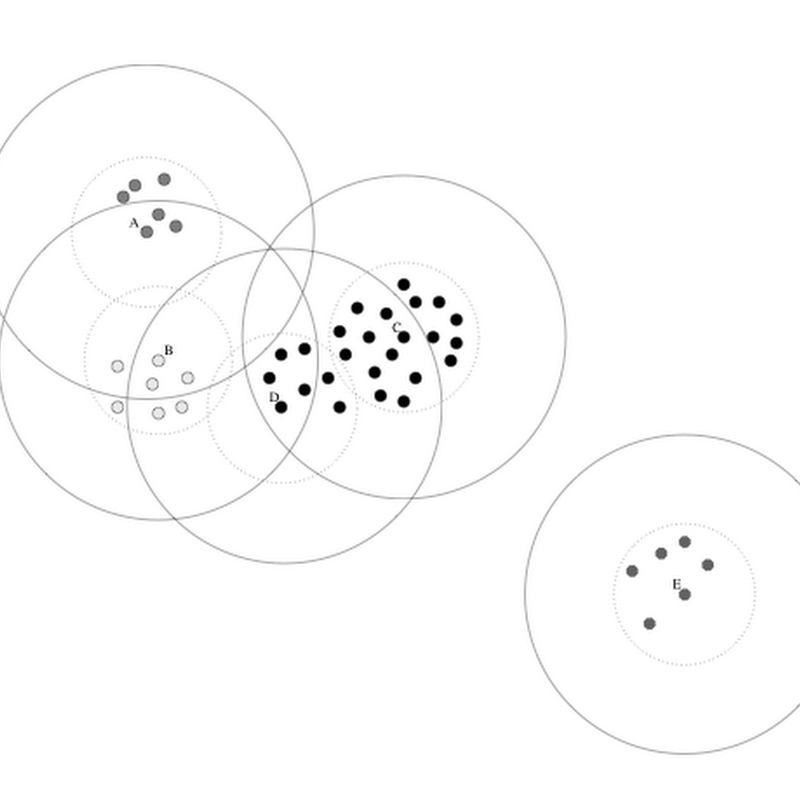

Bibliographic coupling is a term coined by Kessler (doi:10.1002/asi.5090140103) in 1963 as a measure of similarity between documents. If two documents, A and B, cite a third, C, then A and B are coupled. I'm interested in extending this to data, such as DNA sequences and specimens. In part this is because within the challenge dataset I'm finding cases where authors cite data, but not the paper publishing the data.

Lab Times has an interesting article by Ralf Neumann that analyses Europe's publications in evolutionary biology for the period 1996-2006. On page 36 there is a table of the 30 most cited authors in Europe, and the top five most cited papers.

Came across the paper "Using incomplete citation data for MEDLINE results ranking" (pmid:16779053, fulltext available in PMC .The authors applied PageRank (the algorithm Google use to rank search results) to papers in MEDLINE and found that PageRank is robust to information loss. In other words, even if a citation database is incomplete it will do a good job of ranking results.