FAIR is one of those acronyms that spreads rapidly, acquires a life of its own and can mean many things to different groups. A two-day event has just been held in Amsterdam to bring some of those groups from the chemical sciences together to better understand FAIR. Here I note a few items that caught my attention. Fairsharing.org was the basis for several presentations.

This last month, as a follow-up to the preceding post on the colour of flowers, I have been moonlighting by blogging elsewhere. Do go visit my “guerrilla blog” at perivalepark.london. Part of this project involves visiting two “physic or botanic” gardens, which originate from early 17th century explorations of herbs and other botanicals as medicines. Both are very old and their chemistry is indeed fascinating; more of which later.

It was about a year ago that I came across a profusion of colour in my local Park. Although colour in fact was the topic that sparked my interest in chemistry many years ago (the fantastic reds produced by diazocoupling reactions), I had never really tracked down the origin of colours in many flowers. It is of course a vast field.

Ten years are a long time when it comes to (recent) technologies. The first post on this blog was on the topic of how to present chemistry with three intact dimensions.

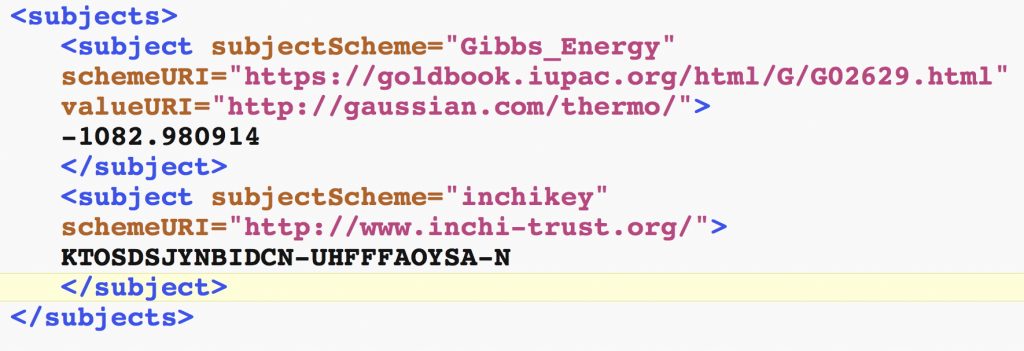

The site fairsharing.org is a repository of information about FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable) objects such as research data. A project to inject chemical components, rather sparse at the moment at the above site, is being promoted by workshops under the auspices of e.g. IUPAC and CODATA and the GO-FAIR initiative.

The molecules below were discussed in the previous post as examples of highly polar but formally neutral molecules, a property induced by aromatisation of up to three rings. Since e.g. compound 3 is known only in its protonated phenolic form, here I take a look at the basicity of the oxygen in these systems to see if deprotonation of the ionic phenol form to the neutral polar form is viable.

In several posts a year or so ago I considered various suggestions for the most polar neutral molecules, as measured by the dipole moment. A record had been claimed[cite]10.1002/anie.201508249[/cite] for a synthesized molecule of ~14.1±0.7D. I pushed this to a calculated 21.7D for an admittedly hypothetical and unsynthesized molecule.

Around the time of the 2012 olympic games, the main site for which was Stratford in east London, I heard a fascinating talk about the “remediation” of the site from the pollution caused by its industrial chemical heritage. Here I visit another, arguably much more famous and indeed older industrial site. The remediation of Stratford involved the removal, cleaning and returning of a vast amount of topsoil, something which was not cheap to do.

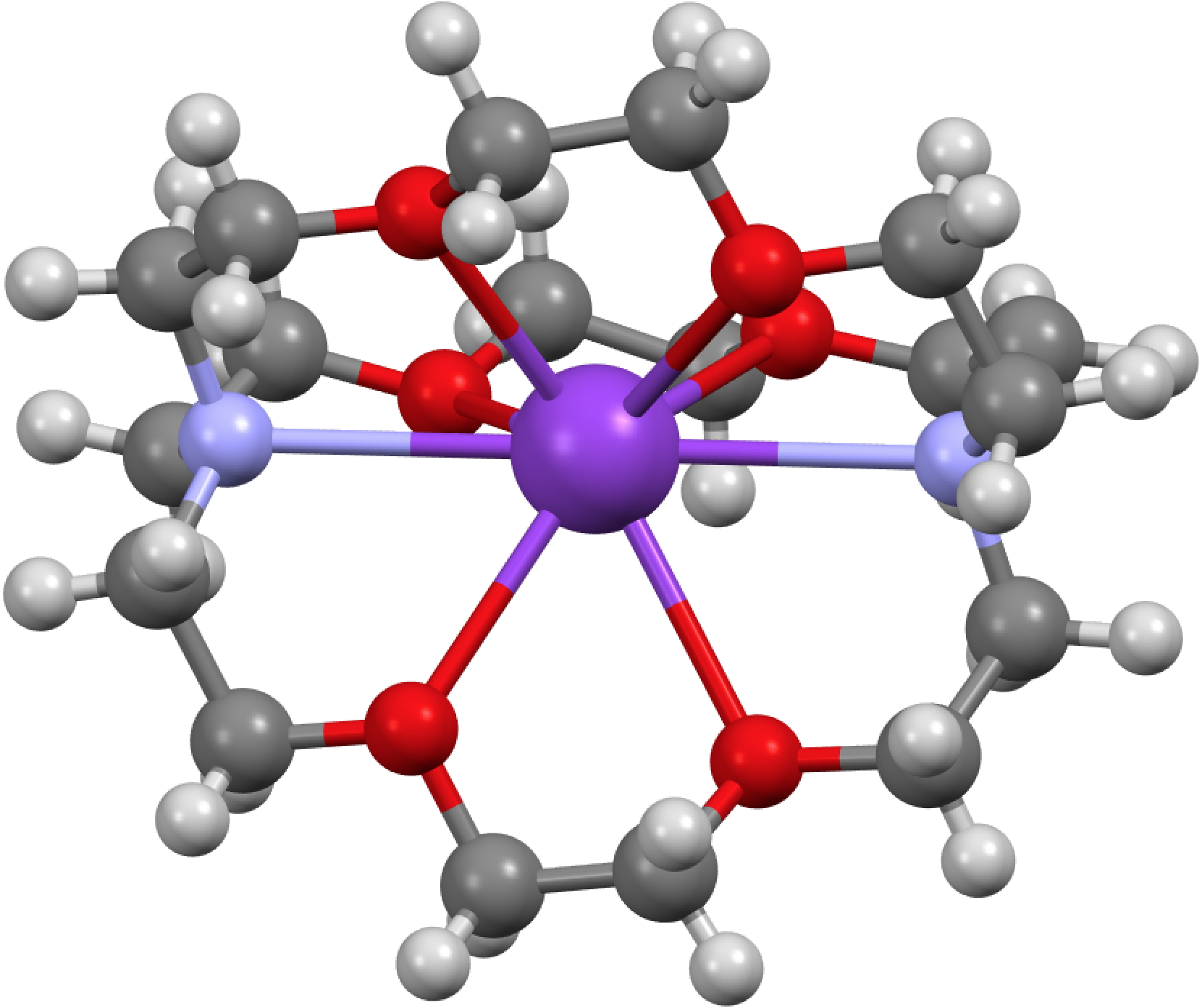

I have posted often on the chemical phenomenon known as hypervalency, being careful to state that as defined it applies just to “octet excess” in main group elements. But what about the next valence shell, occurring in transition metals and known as the “18-electron rule”? You rarely hear the term hypervalency being applied to such molecules, defined presumably by the 18-electron valence shell count being exceeded.