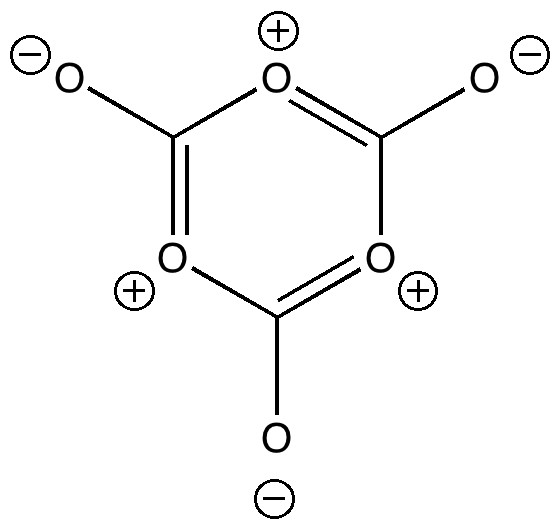

On 8th August this year, I posted on a fascinating article that had just appeared in Science in which the crystal structure was reported of two small molecules, 1,3-dimethyl cyclobutadiene and carbon dioxide, entrapped together inside a calixarene cavity.