When I wrote about Nobel prizes a little while back, I did not expect to return to the subject.

When I wrote about Nobel prizes a little while back, I did not expect to return to the subject.

Who we give prizes to is more a matter of sociology than science. Good science is a prerequisite, but after that it is a matter of which results we value in the here and now. Results that are guaranteed to get a Nobel prize, like the detection of dark matter, attract many suitors who pursue them vigorously. Results that come as a surprise can be more important than the expected results, but it takes a lot longer to recognize and appreciate them.

The time is approaching when Nobel prizes are awarded. This inevitably leads to a lot of speculation and chattering rumor. Last year one publication, I think it was Physics Today , went so far as to publish a list of things various people thought should be recognized. This aspirational list was led, of course, by dark matter.

Given recent developments in the long-running hunt for dark matter and the difficulty interpreting what this means, it seems like a good juncture to re-up* this: The history of science is a decision tree. Vertices appear where we must take one or another branching. Sometimes, we take the wrong road for the right reasons. A good example is the geocentric vs. heliocentric cosmology.

People have been asking me about comments in a recent video by Sabine Hossenfelder. I have not watched it, but the quote I’m asked about is “the higher the uncertainty of the data, the better MOND seems to work” with the implication that this might mean that MOND is a systematic artifact of data interpretation.

Alert reader Dan Baeckström recently asked about NGC 1277, as apparently some people have been making this out to be some sort of death knell for MOND. My first reaction was NGC who? There are lots of galaxies in the New General Catalog (new in 1888, even then drawing heavily on earlier work by the Herschels). I’m well acquainted with many individual galaxies, and can recall many dozens by name, but I do not know every single thing in the NGC.

Something that Sabine Hossenfelder noted recently on Twitter resonated with me: This is a very real problem in academia, and I don’t doubt that it is a common feature of many human endeavors. Part of it is just that people don’t know enough to know what they don’t know. That is to say, so much has been written that it can be hard to find the right reference to put any given fever dream promptly to never-ending sleep.

We are visual animals. What we see informs our perception of the world, so it often helps to make a sketch to help conceptualize difficult material. When first confronted with MOND phenomenology in galaxies that I had been sure were dark matter dominated, I made a sketch to help organize my thoughts.

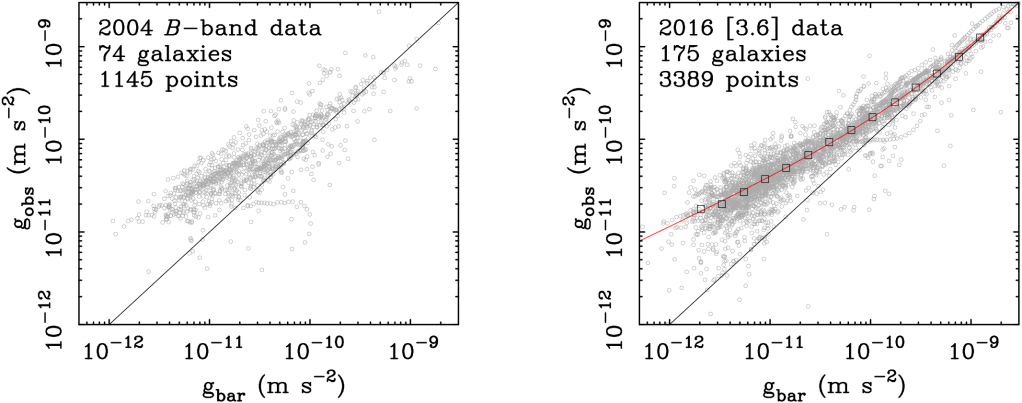

In science, all new and startling facts must encounter in sequence the responses 1. It is not true! 2. It is contrary to orthodoxy. 3. We knew it all along. Louis Agassiz (circa 1861) This expression exactly depicts the progression of the radial acceleration relation.