TW: sarcasm. Today, most research is done by academic labs funded mainly by the government. Many articles have been written on the shortcomings with academic research: Sam Rodriques recently had a nice post about how academia is ultimately an educational institution, and how this limits the quality of academic research. (It’s worth a read;

Corin Wagen

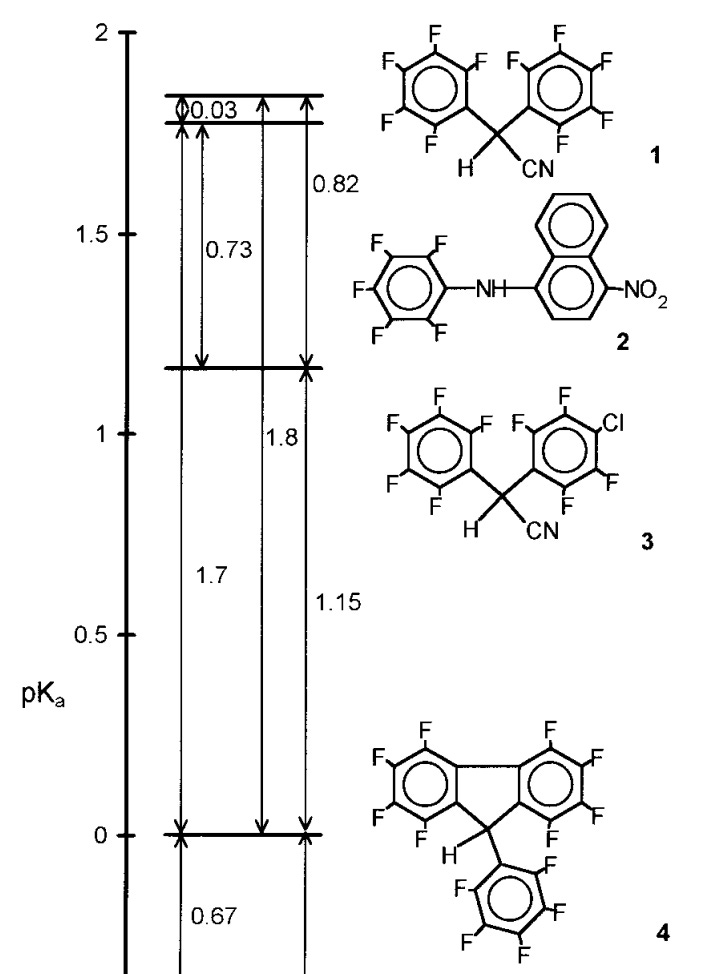

The concept of p K a is introduced so early in the organic chemistry curriculum that it’s easy to overlook what a remarkable idea it is. Briefly, for the non-chemists reading this: p K a is defined as the negative base-10 logarithm of the acidity constant of a given acid H–A: p K a := -log 10 ([HA]/[A-][H+]) Unlike pH, which describes

You are a scientist, not a lab monkey. You ought not to view your degree as “six years of hard labor in the chemistry mines.” Always make time to go to interesting seminars, talk with other people about their research, and read the literature. Otherwise, what’s the point of being a scientist? Only one person is really looking out for your best interests: you.

I’ve been pretty critical of peer review in the past, arguing that it doesn’t accomplish much, contributes to status quo bias, etc. But a few recent experiences remind me of the value that peer review provides: in today’s scientific culture, peer review is essentially the only time that scientists get honest and unbiased feedback on their work. How can this be true?

I first encountered organic chemistry on Wikipedia, my freshman year of high school. The complexity and arcanity of the field instantly attracted me: here was something interesting that I didn’t know about and which didn’t require years of mathematical training to approach (unlike most of physics). I soon started reading about organic chemistry more and more, albeit with no rhyme or reason to my study.

I started this blog one year ago today, with a post on site-selective glycosylation. According to Google Analytics, there have been 24,035 views since then. What have the top posts been?

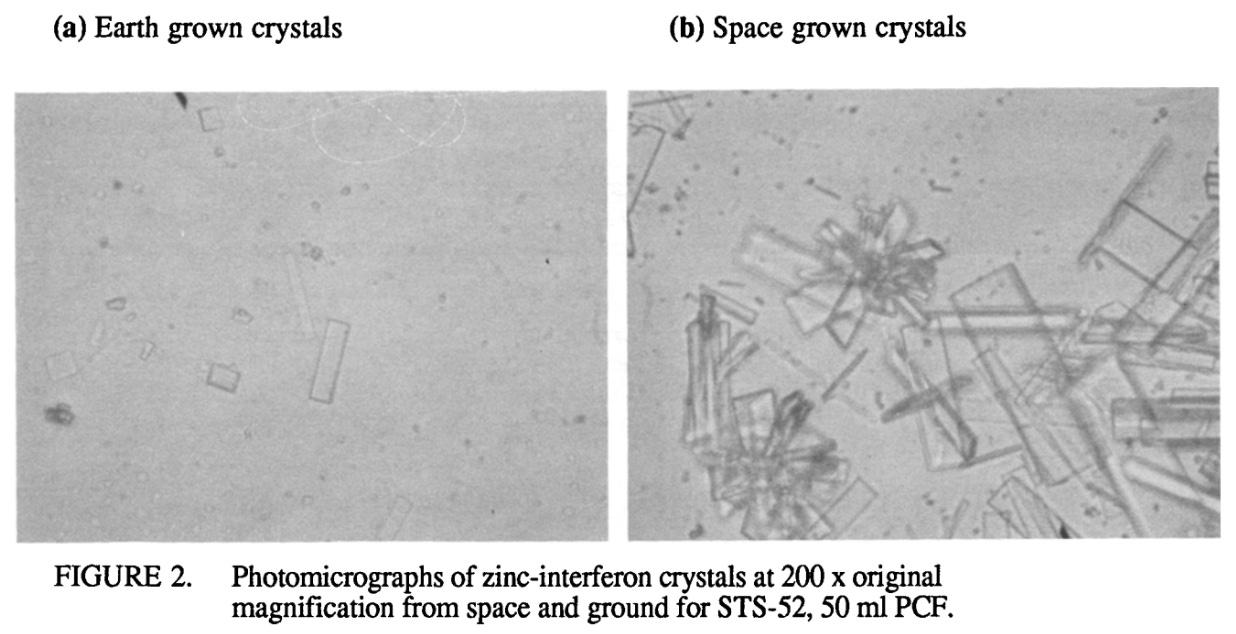

Not Boring recently published a panegyric about Varda, a startup that’s trying to create “space factories making drugs in orbit.” When I first read this description, alarm bells went off in my head—why would anyone try to make drugs in space? Nevertheless, there’s more to this idea than I initially thought.

(with apologies to Maimonides and Nozick) Screening on only one substrate before assessing the substrate scope. This is the “ordinary means” in methods development. Screening on one substrate, but choosing a substrate that worked poorly in a previous study (e.g.). This can be thought of as serial multi-substrate screening, where each substrate is a separate project, but the body of work achieves greater generality over time.

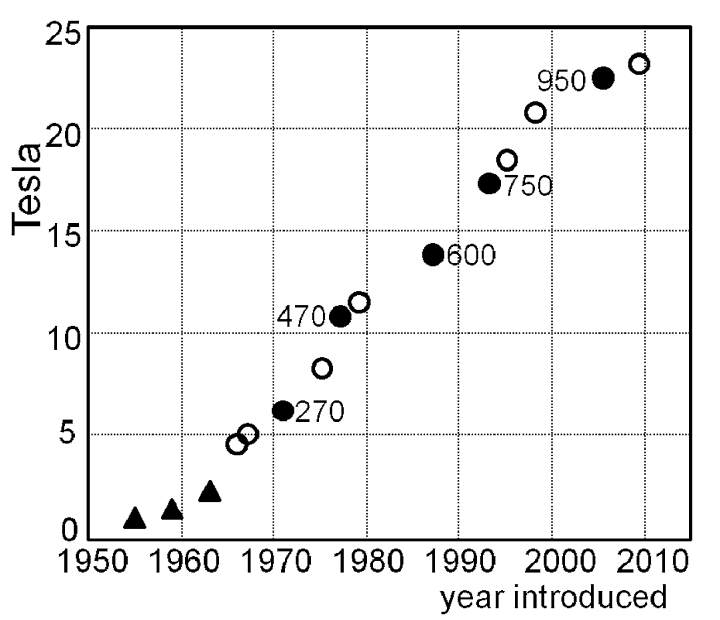

Much ink has been spilled on whether scientific progress is slowing down or not (e.g.). I don’t want to wade into that debate today—instead, I want to argue that, regardless of the rate of new discoveries, acquiring scientific data is easier now than it ever has been. There are a lot of ways one could try to defend this point;

Recently, I wrote about how scientists could stand to learn a lot from the tech industry. In that spirit, today I want to share a book review of Chaos Monkeys: Obscene Fortune and Random Failure in Silicon Valley , Antonio García Martínez’s best-selling memoir about his time in tech and “a guide to the spirit of Silicon Valley” (NYT). Chaos Monkeys is one of the most literary memoirs I’ve read.

Previously, I wrote about various potential future roles for journals. Several of the scenarios I discussed involved journals taking a much bigger role as editors and custodians of science, using their power to shape the way that science is conducted and exerting control over the scientific process.